Brief • 1 min Read

The Harris Poll and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation teamed up to understand how economic inequity has affected Chicago residents’ experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic, neighborhood services, gentrification, local government, and citywide investment initiatives. A survey of over 1,000 residents revealed that although the pandemic is still a primary concern, city leadership must also address issues around economic inequity in Chicago to position the area for a brighter, post-pandemic future.

Evaluating Chicago Wealth Distribution

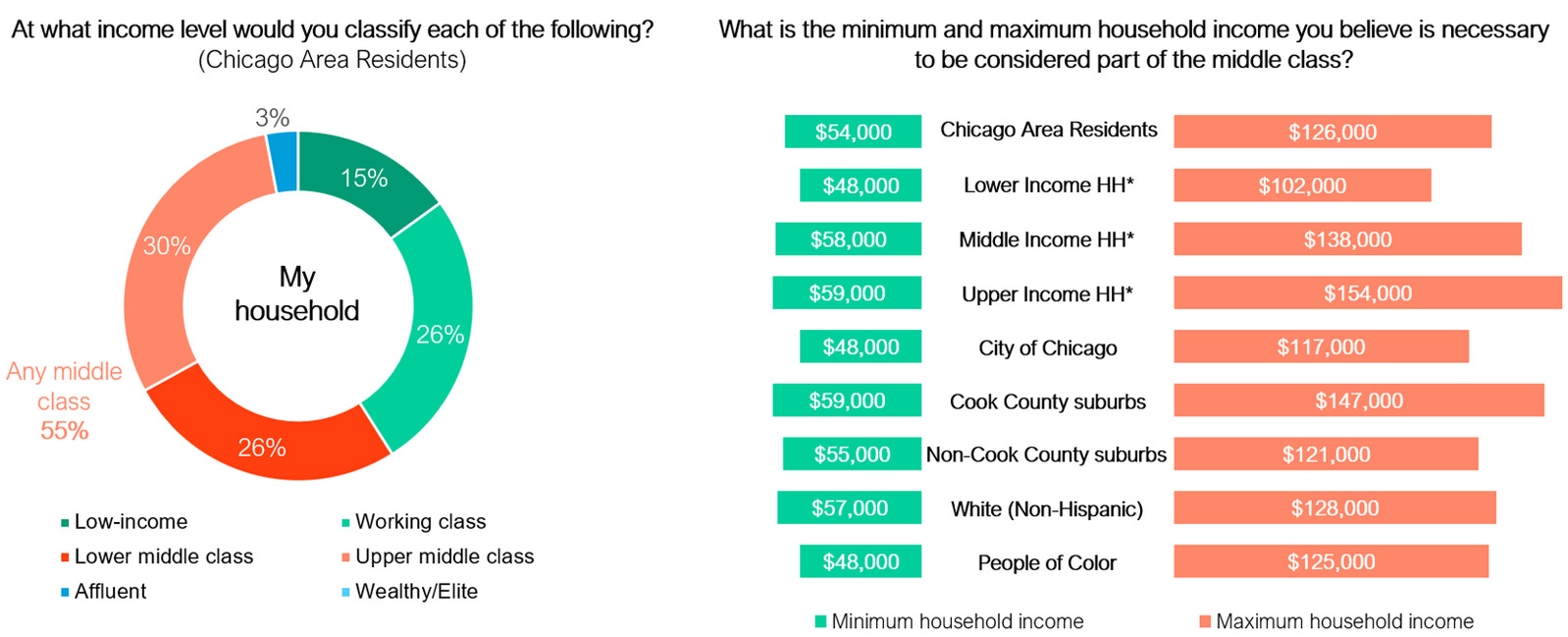

Overall, residents tend to consider the Chicago area to be middle class – though the definition of such is subjective. Understanding what parameters residents use to define the middle class will be used to create an economic profile for the area and its residents, ultimately allowing for comparison between the city, the suburbs, and the rest of the country.

More than half (55%) of Chicago area residents consider themselves to be members of the middle class. However, this self-description does vary by region. Fifty-eight percent of Cook County suburbanites and 61% of suburbanites from the outer lying counties identify as middle class. City residents, however, report a nearly even split. Forty-seven percent of those living in the city of Chicago believe that they live in a middle-class household while another 50% identify as lower income (i.e., low-income or working class).

When asked to define the middle class in monetary terms, Chicagoans considered households with an annual income between $54,000 and $126,000 to be members of the middle class. However, this range also varies based on personal experiences (e.g., current financial situation, estimated cost of living). For example, when looking specifically at residents of Cook County, those living in the City of Chicago set lower middle-income boundaries ($48,000 – $117,000) than suburbanites ($59,000 – $147,000).

Digging Deeper: Very few residents see themselves as affluent or wealthy. In fact, even those who self-identify their household as upper income use a higher maximum for what qualifies as middle income.

*Class/income level is based on how residents self-identify. This definition is not based on actual household income.

BASE(S): Chicago area residents (n=1,004), Low-income HH* (n=155), Working class HH* (n=258), Lower middle class HH* (n=256), Upper middle class HH* (n=301), Affluent HH* (n=33), Wealthy/elite HH* (n=2), Lower income HH* (net) (n=413), Middle income HH* (net) (n=557), Upper income HH* (net) (n=34), City of Chicago (n=333), Cook County suburbs (n=263), Non-Cook County suburbs (n=408), White (n=637), People of color (n=367)

Looking beyond their own city, very few Chicagoland residents (7%) believe that middle class Chicagoans are better off financially relative to members of the middle class in the rest of the country. Additionally, while most Chicago residents (55%) think middle class households across the country are in a similar financial position, data from the US Census Bureau reveal that neither of these assumptions is true. The median household income in the City of Chicago falls below national figures by more than 10%; Median household income in the U.S. hovers around $65,000 while the median income in Chicago is only $58,000.

Economic Mobility and Assistance

In general, Chicagoland residents are confident in their ability to afford essential expenses, but far fewer report having money left over at the end of every month, slowing economic mobility.

More than 80% report being able to afford the essentials every month, but only 63% agree they have money left over after paying for the essentials.

As a result, many Chicagoans may not be investing heavily in their savings. Just half are comfortable with the level of emergency savings that their household currently has set aside. Additionally, only three in five area residents agree that if they needed a personal loan from a bank, it would be easy for them to qualify.

Neighborhood Perceptions

The way that residents feel about their neighborhood isn’t dictated solely by income level. Personal financial situation and economic mobility go hand-in-hand with lifestyle and living situation. With the population in the City of Chicago shrinking, neighborhood-level concerns expressed by residents can help identify potential areas of focus for local decisionmakers.

The vast majority of area residents say they are proud to live in their current neighborhood (82%). This may explain why most Chicago area residents are long-time residents. More than half (56%) have lived in their neighborhood or town longer than 10 years; this is slightly higher among city residents at 63%.

Even so, many area residents still consider moving both within the Chicago area and away from it. In the past year, 31% of city residents have thought about moving away from the greater Chicago area (e.g., to somewhere else in Illinois, to another state). Another 16% have thought about moving to the suburbs, and 19% have thought about moving to another neighborhood within city limits.

Among those in the suburbs, more than a third (36%) have thought about moving away from the greater Chicago area in the past year. Another 15% have considered moving from their current neighborhood to another suburb. Only 9% have thought about moving into the city.

However, perhaps given the pandemic, few have acted on their considerations. Just 11% of city residents have moved around within the area, and just 5% of suburban residents have done the same.

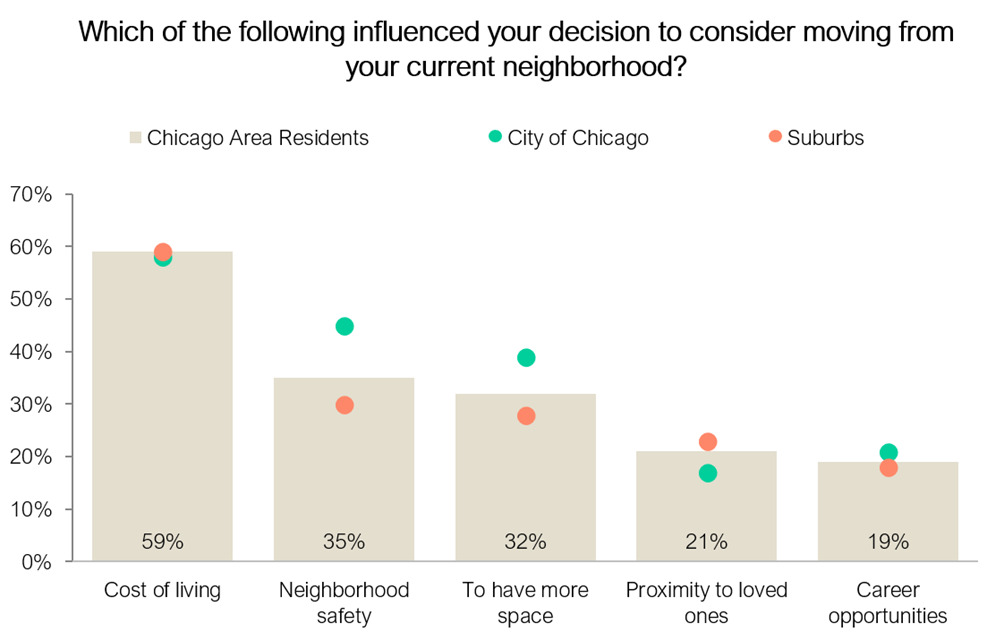

Digging Deeper: More than half of Chicagoans that moved or considered moving in the past year did so, at least in part, because of their neighborhood’s cost of living. Other top reasons, especially for those living in the city, included neighborhood safety and gaining more space.

BASE(S): Chicago area residents (n=1,004), City of Chicago (n=333), Suburbs (n=671)

Key Neighborhood Issues

Life in one’s neighborhood is often a key indicator in determining whether a resident will stay in an area, and Chicago area residents — despite their strong sense of neighborhood pride — also have their complaints.

Overall, the most common issues that residents say impact their neighborhood are public safety (28%), dissatisfaction with local leadership (25%), a struggling local economy (25%), and housing (24%).

Unsurprisingly, city residents, specifically, felt the influence of common Chicago issues much more strongly than suburban residents. Take again as examples public safety (50% city vs. 16% suburbs), dissatisfaction with local leadership (32% vs. 22%), the struggling local economy (30% vs. 22%), and housing (30% vs. 21%).

When asked to identify the issue that impacts their neighborhood the most, those in the city mentioned public safety (31%) while those in the suburbs say it’s the struggling local economy (15%).

When looking specifically at the local economy, most area residents (83%) agree high property taxes are hurting the local economy and 53% agree larger economic trends (i.e., state, national, or global economic issues) have more influence over issues in Chicago than over issues in other U.S. cities.

While they believe Chicagoland may be struggling economically, area residents maintain a more positive view of their own, respective neighborhoods. Most residents (65%) actually think their neighborhood’s economy is healthier than the economies of other Chicago neighborhoods. Additionally, the same amount believes their neighborhood is on the upswing, and just over half (54%) agree their neighborhood has changed for the better over the last five years.

Gentrification

Nevertheless, a third (34%) of all area residents agree that gentrification poses a larger threat to their neighborhood than other neighborhoods in Chicago; this is higher among city residents at 44%. Residents of color also agree with this sentiment more often than White residents (45% vs. 28%).

Just under a third of area residents say racial/ethnic diversity is declining in their neighborhoods (31%), and another 52% say they cannot afford to buy a home in their neighborhood. The latter is even higher for city residents at 60%. Compared to 53% of suburb residents, 63% of city residents agree the cost of living in their neighborhood is increasing faster than it is in other Chicago neighborhoods.

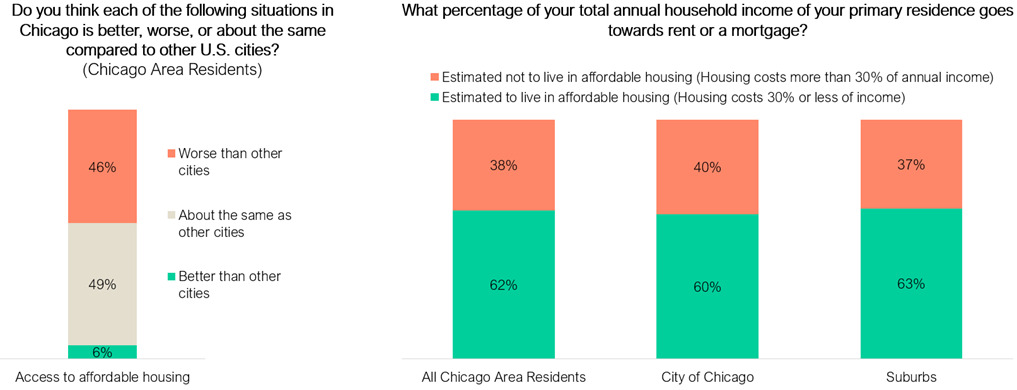

Digging Deeper: Although nearly half of all area residents say the affordable housing situation is worse in Chicago than in other cities, approximately two-thirds appear to live in affordable housing according to federal thresholds. This holds regardless of whether one lives in the city or in the suburbs.

The federal government establishes the threshold for unaffordable housing as any housing that is greater than 30% of annual household income. For this study, respondents were asked to estimate what percentage of their income goes towards mortgage and rent payments. Residents were not made aware that the threshold for unaffordable housing is 30% of annual household income.

BASE(S): Chicago area residents (n=1,004), City of Chicago (n=333), Suburbs (n=671)

Given concerns about gentrification, it may be some comfort to hear that residents throughout the Chicagoland area say small or locally owned business are still the largest share of businesses in their neighborhoods (42% among city residents, 34% among Cook county suburb residents, and 35% among all non-Cook county residents).* However, 69% of all area residents note that small businesses in their neighborhoods are struggling to get by.

Still, three-quarters (73%) of all residents feel optimistic about the future of their neighborhood. This viewpoint holds across the city and suburbs, but it is generally higher among White residents, older residents, and those with higher household incomes.

The Children Are the Future

Determining economic mobility potential is a key component of a neighborhood’s outlook. Overall, when assessing key indicators of economic mobility of children in their neighborhood, most residents believe their neighborhood’s children face a very bright future. When asked about the children in their neighborhoods

- 80% of area residents agreed they came from stable and supportive homes,

- 70% agreed they interact with other children from all walks of life (e.g., race, income, religion),

- 74% agreed they attend high quality schools,

- 78% agreed they have access to the right people or resources that will help them achieve their personal goals,

- 85% agreed they will be able to pursue higher education,

- 69% agreed that as adults, these children would have a higher standard of living than their parents currently do, and

- 84% agreed they would live long and healthy lives.

Although agreement for these statements was lower among city residents, a majority (approximately two-thirds) still agreed on these points, too.

Moreover, across all area residents, 69% agree that, as adults, their children will have a better standard of living than they do.

COVID-19: Then and Now

While the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic has likely passed, leaders and residents in the Chicagoland area now need to determine a viable path forward. Evaluating the equity of resource allocation across neighborhoods can help decisionmakers establish benchmarks as communities enter the next phase of recovery.

Aside from medical services/resources, such as getting tested for COVID-19 (54%) and getting vaccinated against COVID-19 (75%), a significant share Chicago area residents sought emergency food supplies (21%), mortgage or utility assistance (15%), and loan forgiveness or loan payment pauses (15%) during the pandemic.**

City residents (25%) and residents of color (27%) sought emergency food at higher rates than their respective counterparts, suburban (18%) and White residents (17%). Residents of color (18%) also over-indexed on seeing mortgage/utility assistance compared to White residents (12%). Perhaps surprisingly, both those with annual HHI<$50k (16%) and HHI 100K+ (17%) most often reported seeking mortgage or utility assistance compared to those with more middle incomes. Younger residents (19% of Gen Z, 25% of Millennials) and those of color (20%) also over-indexed on seeking loan forgiveness or payment pauses compared to their respective counterparts (less than 14% of those over 40, 12% of White residents).

When thinking about how others fared during the pandemic, depending on the resource, anywhere between one in 10 and one in three residents reported it took more effort for them to access services and resources during the pandemic compared to Americans living in other U.S. cities and compared to other Chicago residents.

Across resources, common reasons for extra required effort included an inability to make appointments or meetings to obtain services (31%), discomfort going to a particular place to obtain a resource or service (22%), and general difficulty finding or accessing necessary supplies like food, PPE, or vaccinations (9%-22%). About one in 10 also referenced lacking access to transportation.

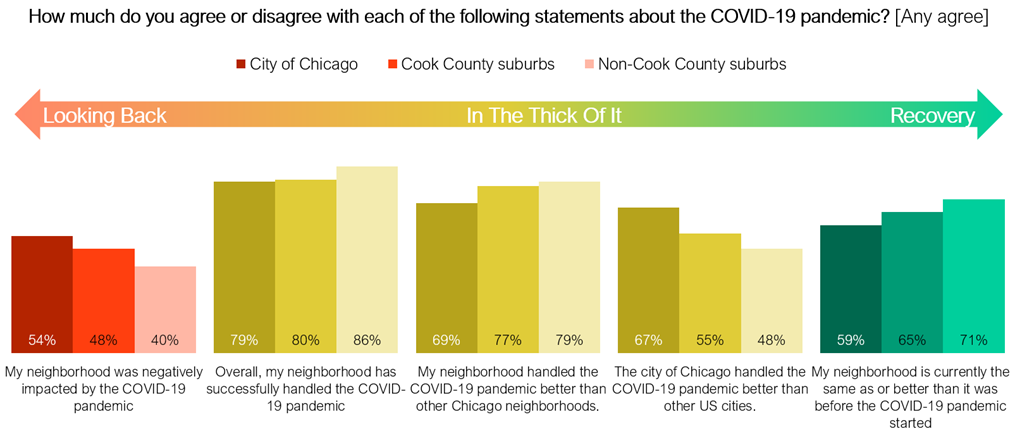

Digging Deeper: Those living in city neighborhoods often felt more negatively impacted by the pandemic, yet residents are largely aligned that their neighborhoods were successfully able to handle and recover from the pandemic. Those living outside city limits had a less positive view of city government’s ability to handle the pandemic though.

BASE(S): City of Chicago (n=333), Cook County suburbs (n=263), Non-Cook County suburbs (n-408)

Managing Neighborhood Well-Being

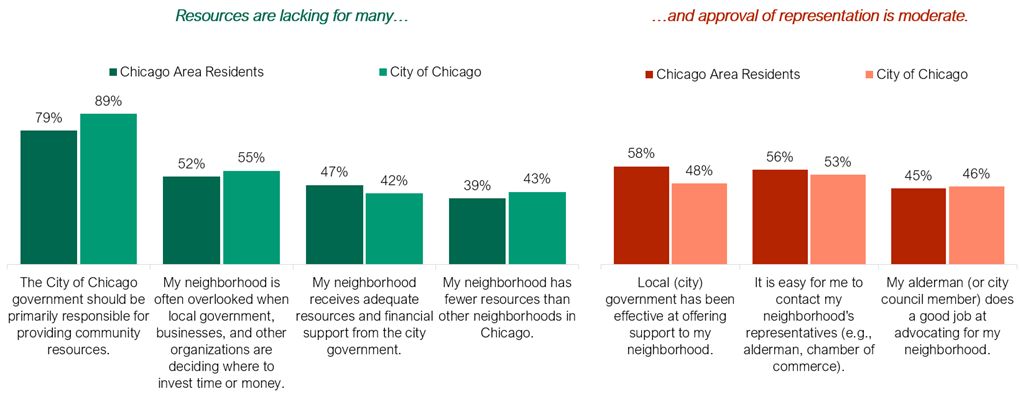

Currently, half of Chicagoland residents feel that their neighborhood is overlooked when government groups, businesses, and other organizations make investments in the community. In order to course-correct, local decisionmakers will need to understand which parties residents believe should be responsible for managing neighborhoods as well as how effective those parties have been so far.

A large majority of all area residents (79%) agree that the City of Chicago government should be primarily responsible for providing community resources; this is even higher among city residents at 89%. However, only 47% of all area residents agree that their neighborhood receives adequate resources and financial support from the city government. This is even lower for city residents at 42%.

Moreover, 52% feel that their neighborhood is often overlooked when local government, businesses, and other organizations are deciding where to invest time or money.

Less than half of all area residents reported having entertainment options, racial/ethnic diversity, well-rated public schools, job opportunities, arts/cultural organizations, and affordable housing in their neighborhoods. Specifically, among residents in the city of Chicago, in addition to the previously mentioned resources, less than half of residents also reported having public safety and well-maintained infrastructure in their neighborhoods.

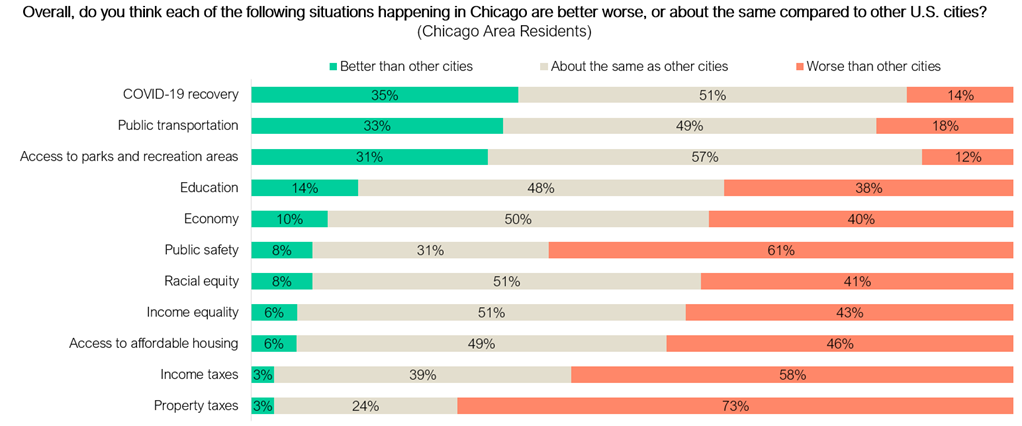

Additionally, Chicago area residents feel that property taxes (73%), public safety (61%), income taxes (58%), access to affordable housing (46%), and income inequality (43%) are worse in Chicago than in other U.S. cities. Other situations including racial equity, the economy, and education were also not far behind in local dissatisfaction.

In fact, aside from the pandemic recovery, the only situations where residents most often say Chicago is doing better than other U.S. cities are access to parks and recreation areas (31%) and public transportation (33%).

BASE(S): Chicago area residents (n=1,004)

Reimagining Neighborhood Support

Though the level of need varies by neighborhood type, Chicago area residents want to see more job opportunities (34%), affordable housing (34%), well-maintained infrastructure (29%), entertainment options (e.g., movie theaters, sports stadiums) (29%), restaurants (28%), and public safety (27%) in their neighborhoods. Overall, they also prefer more local businesses (28%) to other retail stores (23%).

More specifically, city residents want to see more investment in solutions to economic inequity in Chicago. Compared to suburban residents, city residents especially want to see more job opportunities, (29% vs. 44%, respectively) affordable housing (30% vs. 42%), well-maintained infrastructure (25% vs. 37%), and well-rated public schools (20% vs. 33%) in their neighborhoods.

The Role of Government

Overwhelmingly, Chicago area residents prefer a level of the government (local, state, or federal) handle key city services or issues as opposed to the private sector.

More than half of all area residents hold local (city) government primarily responsible for access to parks and recreation areas (68%), public safety (64%), and public transportation (63%). Residents also most often say local government should be primarily responsible for property taxes (47%), access to affordable housing (40%), and racial equity (36%).

Although income taxes and income inequality were areas where residents say Chicago fares worse than other cities, residents are more likely to prefer state government (45% and 36%, respectively) take on responsibility for such issues compared to local government (20% and 22%, respectively).

Neighborhood representatives could also do a better in the eyes of Chicago residents, especially among city residents. Compared to 63% of suburban residents, less than half (48%) of city residents say local government has been effective at offering support to their neighborhoods. City residents, specifically, are much more approving of local/small businesses, schools/universities, community volunteers, and nonprofits than local government when it comes to neighborhood support.

Even though most area residents (56%) agree that it is easy to contact their neighborhood’s representatives (53% for city residents), only 45% of all area residents (and 46% of city residents) say their alderman does a good job at advocating for their neighborhood.

Most residents agree city government should be primarily responsible for providing community resources, but less than half feel their neighborhood receives adequate resources, support, and representation.

BASE(S): Chicago area residents (n=1,004), City of Chicago (n=333)

Area residents really do want local government to take the lead on key city issues. This gives city leadership the perfect opportunity to highlight – and potentially expand upon – the ongoing initiatives it’s already running.

Investment Initiatives

Steps are being taken by local government to improve quality of life in the greater Chicago area, but the perceived effectiveness of those steps remains to be seen. Overall awareness of key social programs is lacking, highlighting a missed opportunity for local leaders to connect with residents seeking more support.

At best, Chicagoland residents tend to know social programs in name only; 43% believe that they have heard of at least one initiative surveyed.***

Reported familiarity is lower. For example, of surveyed initiatives, Chicago Connected and My CHI. My Future. yielded the highest awareness at 12% each. Only 9% of area residents state they have heard of INVEST South/West.

However, demonstrated familiarity is even lower. Of the residents who claim to be familiar with the primary goal of at least one surveyed initiative, only 5% can correctly match the surveyed programs to their purpose.

These social initiatives can have a significant positive impact, particularly in marginalized communities. However, it’s clear that community leaders still need to bridge the gaps between residents, available resources, and communication about access.

A Better Normal

The pandemic has forced Chicago to reckon with the consequences of local economic inequity. Now, it needs to act. City leaders will need to meet area residents where they are and recognize the nuance in neighborhood-level concerns. They will also need to understand how to apply the right solutions in neighborhoods, within city limits, and across the entire Chicagoland region. Moreover, city leadership needs to improve how it communicates the availability and success of its initiatives.

After the pandemic, Chicago’s new normal should be a better normal. Such steps will give local leaders an opportunity to reduce economic inequity in Chicago and build trust among area residents that will last long after the pandemic has ended.

*It is possible that small or local business can still be geared to more affluent customers, thereby contributing to gentrification trends in neighborhoods. However, note that across city and suburbs, residents said that about one in 10 stores in their neighborhoods were specifically luxury retailers.

**For this report, the ongoing pandemic is defined as March 2020 to July 8, 2021. Given the end date for fielding, sentiments and perceptions after July 8, 2021, have not been captured.

***Surveyed initiatives include Chicago Connected, My CHI. My Future., INVEST South/West, Together We Heal, We Will Chicago, and We Rise Together.

Methodology

This survey was conducted online within the United States between June 21, 2021, and July 8, 2021, among 1,004 adults (aged 18 and over) in the Chicago DMA by The Harris Poll on behalf of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Figures for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, region and household income were weighted where necessary to bring them into line with their actual proportions in the population. Propensity score weighting was used to adjust for respondents’ propensity to be online.

All sample surveys and polls, whether or not they use probability sampling, are subject to multiple sources of error which are most often not possible to quantify or estimate, including sampling error, coverage error, error associated with nonresponse, error associated with question wording and response options, and post-survey weighting and adjustments. Therefore, the words “margin of error” are avoided as they are misleading. All that can be calculated are different possible sampling errors with different probabilities for pure, unweighted, random samples with 100% response rates. These are only theoretical because no published polls come close to this ideal.

Respondents for this survey were selected from among those who have agreed to participate in our surveys. The data have been weighted to reflect the composition of Chicago’s adult population. Because the sample is based on those who agreed to participate in the online panel, no estimates of theoretical sampling error can be calculated. For more information on methodology, please contact Dami Rosanwo or Madelyn Franz.

Subscribe for more Insights

Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest trends in business, politics, culture, and more.

Download the Data

Get the full data tabs for this survey conducted online within the United States between June 21, 2021, and July 8, 2021, among 1,004 adults (aged 18 and over) in the Chicago DMA by The Harris Poll on behalf of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Download

Subscribe for more Insights

Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest trends in business, politics, culture, and more.

Download the Data

Get the full data tabs for this survey conducted online within the United States between June 21, 2021, and July 8, 2021, among 1,004 adults (aged 18 and over) in the Chicago DMA by The Harris Poll on behalf of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

DownloadRelated Content