Brief • 5 min Read

The Harris Poll and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation teamed up to understand how Chicago residents feel about the city’s biggest challenges regarding public safety. A survey of nearly 1,000 residents revealed a city troubled by gun violence, little sense of community, and complicated police-resident relations. Although opinions and suggested solutions diverged based on lived experiences, what Chicagoans did agree on is that gun violence, race, and policing are heavily intertwined and that the laws, systems, and organizations that influence these issues need reform.

Residents agree the city has a gun problem

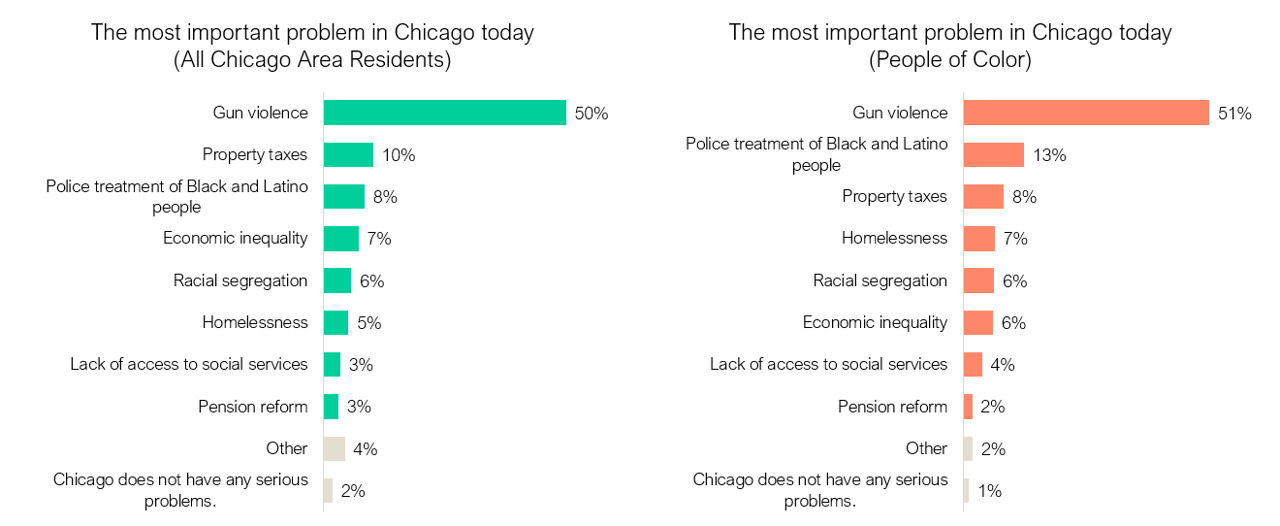

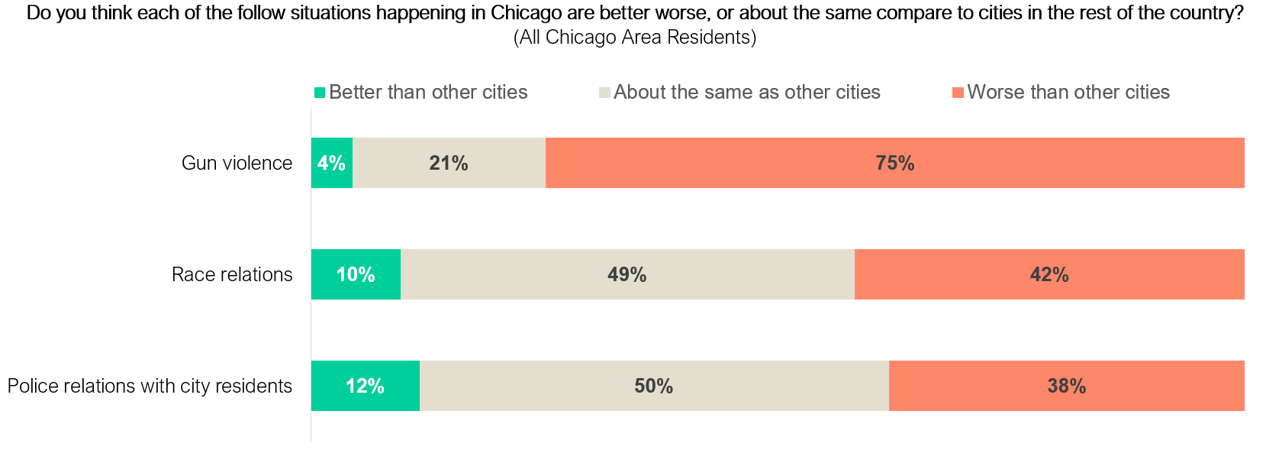

Gun violence is overwhelmingly viewed as Chicago’s most important issue. Fifty percent of all Chicago area residents say it is the most important problem in Chicago today — five times higher than the next most mentioned problem, property taxes. In fact, 75% of all residents think gun violence is worse in Chicago than in other cities. It’s no surprise, then, that the vast majority (96%) agree that gun violence in Chicago needs to be reduced.

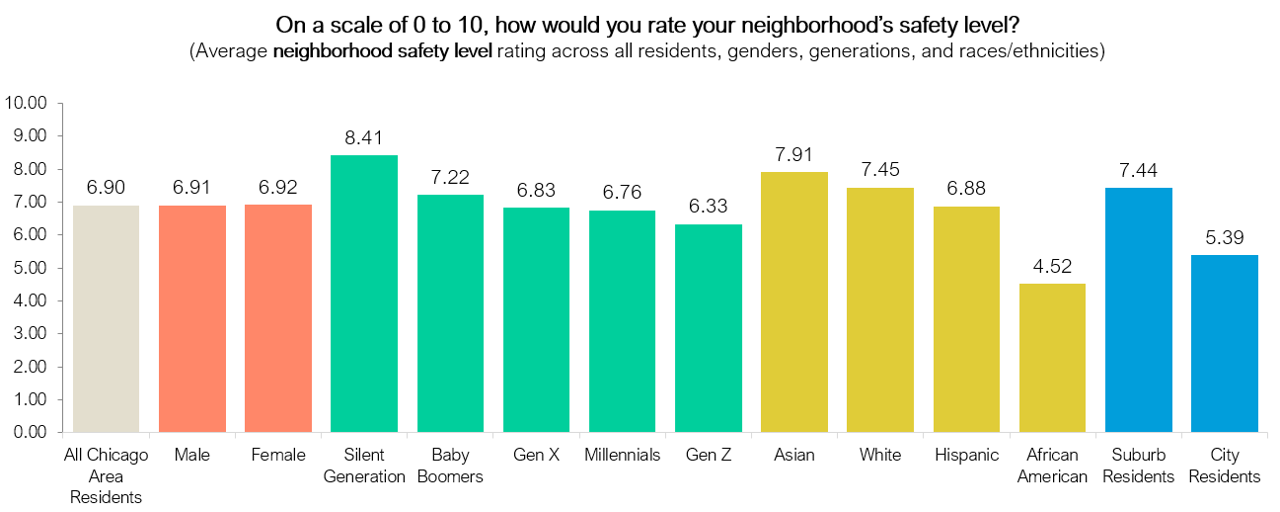

Overall, Chicago residents feel a moderately high level of safety in their neighborhoods. On a scale of 0 (not at all safe) to 10 (completely safe), the level of neighborhood safety for all residents averages at 6.9 out of 10 — though this rating varies across racial, generational, and socioeconomic lines with younger, non-White, and lower income residents giving lower safety ratings.

How does the city increase the sense of resident safety, especially with regards to gun violence? Chicago residents want to see fewer guns on the street, and they demand that those who do possess guns prove they are responsible with their weapons. They view background checks for all gun sales (63%) and higher penalties for gun-related crimes (60%) as the primary tactics for dealing with gun violence. In fact, they view these legislative tactics as even more effective than increased police presence (55%) when it comes to reducing gun violence.

That being said, 82% of Chicago residents still agree increased police presence is necessary for reducing gun violence in the city. Unfortunately, Chicago residents are divided on solutions involving their comfort level with the use of police.

With police-resident relations, it’s a tale of two cities

Complicated police-resident relations start with a general lack of community across the area. Most Chicago residents (53%) disagree that there is a strong sense of community across Chicago.

Race relations also remain a problem in the eyes of residents with 42% of all residents saying race relations are worse in Chicago than in other U.S. cities. Nearly three-quarters (72%) disagree race relations in Chicago are good right now, and 66% disagree that compared to this time last year, race relations have improved. More than half (57%) also disagree race-related issues in Chicago are due to a few bad actors instead of systemic issues.

A similar story appears with police-resident relations. Although 50% of residents say police relations with city residents are on par with other U.S. cities, a large plurality (42%) believe police-resident relations are worse in Chicago, indicating many feel there is work to be done.

Ultimately, this study found that, in general, the idea of public safety representatives makes Chicagoans feel safer, but actual police officers do not always make city residents feel safe.

Overall, most residents agree members of the Chicago Police Department are handling their job well (62%) and that when they see a police officer in their neighborhood, they feel safer (79%). Most also agree police are often able to solve crimes that occur in the city (58%), and that the police have been effective at reducing or preventing crime in their neighborhood (63%).

Unsurprisingly, residents of color agree less often with such perspectives. Compared to 88% of White residents, only 67% of residents of color agree that when they see a police office in their neighborhood, they feel safer. Additionally, compared to 71% of White residents, only 53% of residents of color agree that Chicago police have been effective at reducing crime in their neighborhoods. In fact, 60% of African American residents disagree that this is the case.

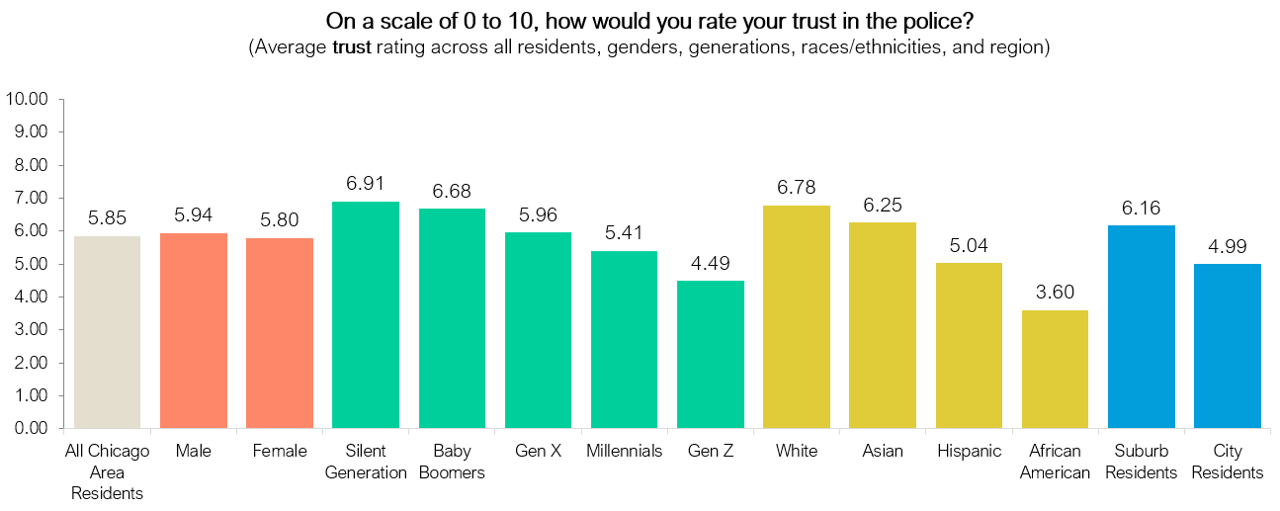

Such differences are also reflected in the level of trust residents have in the police. On a scale of 0 (do not trust at all) to 10 (completely trust), overall resident trust in the police averages a 5.9 out of 10. White residents have the highest level of trust in the police (6.8) while Black residents have the lowest (3.6). In fact, 21% of Black residents and 13% of Hispanic residents say they have no trust (0 out of 10) in police (compared to just 2% of White Chicago area residents).

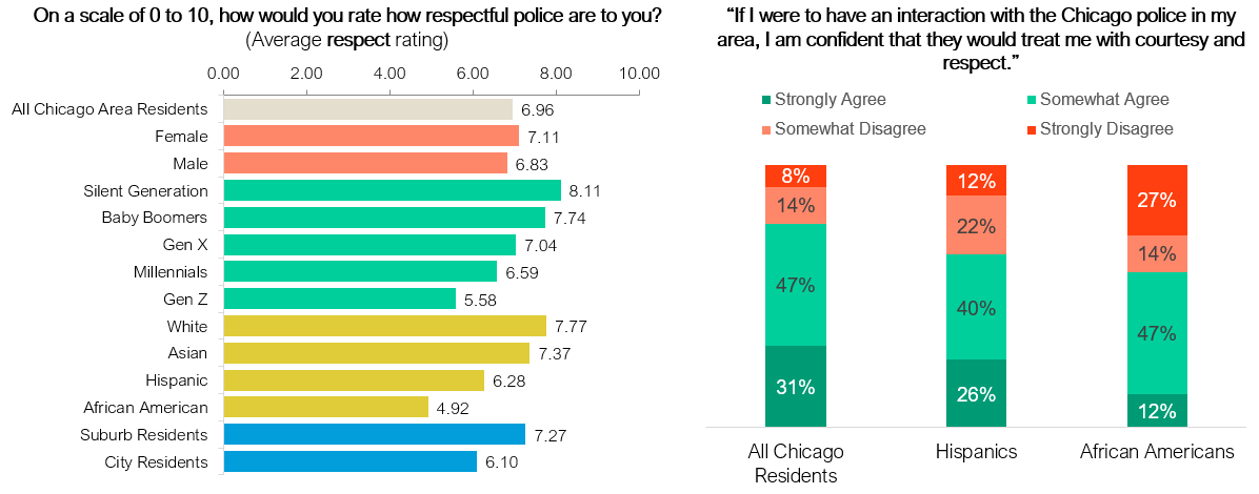

This lower level of trust is also affected by police treatment. On a scale of 0 (not at all respectful) to 10 (completely respectful) African American (4.9), Hispanic (6.3), and Asian (7.4) residents all rate how respectful police are to them as lower that White residents (7.8). Additionally, compared to 88% of White residents, only 66% of Hispanics and 59% of African Americans are confident that if they had an interaction with the police, the police would treat them with respect.

African American and Hispanic residents report negative experiences with the police at twice the rate of White residents (31% and 24% vs. 8%, respectively). They also display greater anxiety towards reporting police misconduct due to fear of retaliation. Fifteen percent of all residents say that if they were to report police misconduct to the Chicago Police Department, they believe they would receive retaliation from officers for filing a complaint. This number is highest for Hispanics at 22%. In fact, 23% of Hispanic residents say there has been an actual instance where they were afraid to report police misconduct due to police retaliation compared to just 11% of all Chicago residents.

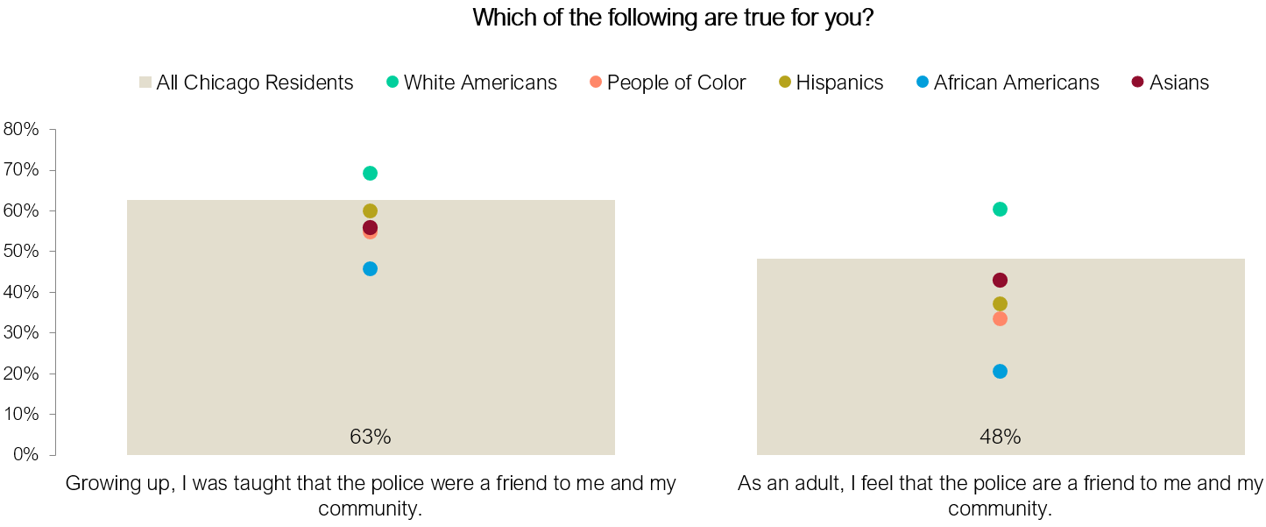

Digging Deeper: As residents grow older, how they view their relationships with police officers changes. Although growing up, most residents were taught to view police as friends, that belief holds less often now that residents are adults.

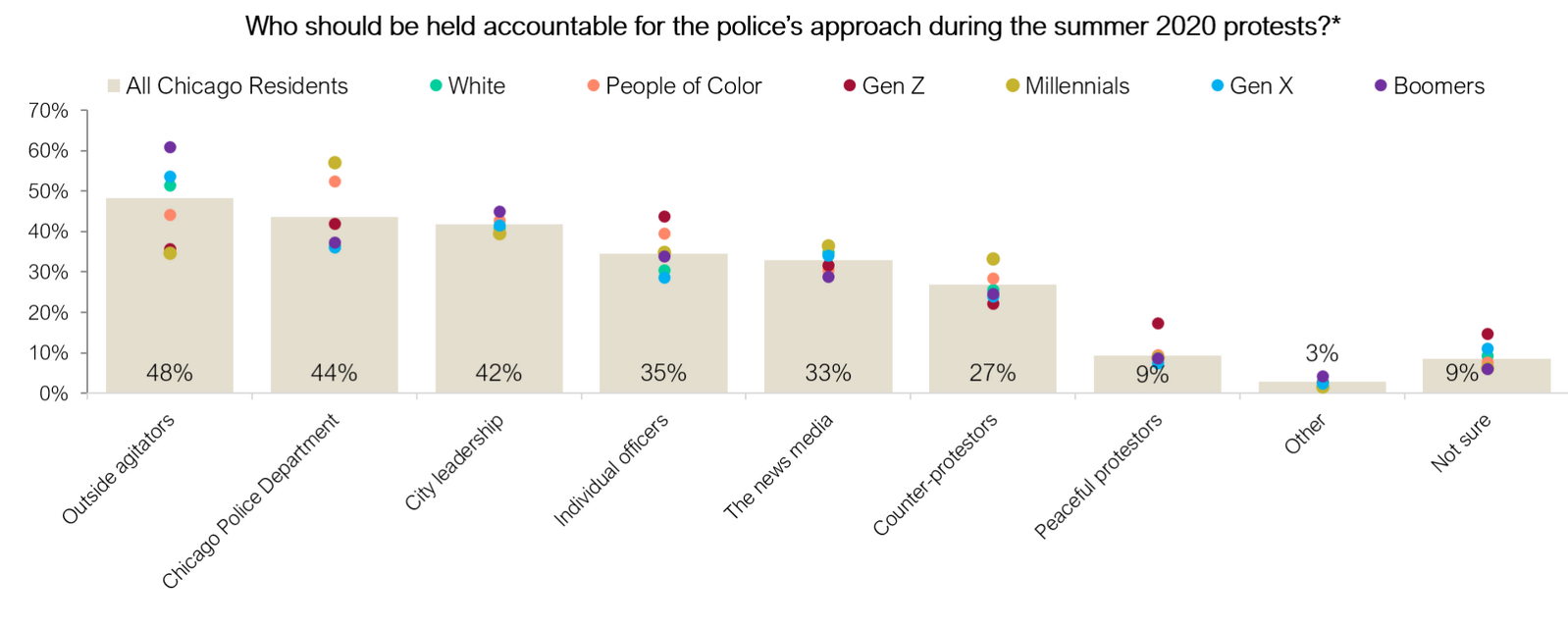

It is such differences in treatment that led to calls for police reform last summer and the subsequent response by Chicago police. Overall, Chicago area residents are equally divided on their approval of the way the Chicago Police Department handled the summer 2020 protests. Most frequently, they hold outside agitators (48%), the Chicago Police Department (44%), city leadership (42%), and individual officers (35%) accountable for the CPD’s approach with varying reasons as to why.* Such controversy around the police department’s approach has also led to increased discussion over police department funding and policies.

Digging Deeper: Chicago area residents vary in who they hold accountable for how the Chicago Police Department approached the Summer 2020 protests. With regards to police-resident relations and potential reforms, it is important to focus on those who hold the police department, city leadership, and individual officers accountable and why they hold those views because it is these three groups that will be key in repairing police-resident relations.

Top reasons for why nearly half of all residents held the CPD responsible for the approach it took to the summer protests include not being trained well enough to deal with protests of that size (47%), officers improperly trained on mass arrest procedures (46%), and that the pole were unprepared for a possibility of mass arrests.

More than two in five residents think city leadership should be held accountable for the CPD’s approach, most often citing an inability to handle the protests (48%) and an inability to establish police accountability (43%).

Over a third of area residents think individual officers should be held accountable, most often citing that they were not trained to deal with situations like the protest (50%), they were too aggressive (49%), and they were prejudiced (45%).

Note, the findings from this questions should not be interpreted as defining who is actually responsible for the CPD’s approach, but rather the findings should be interpreted as what residents’ opinions are about who should be held accountable based on their personal experiences and external influences, such as the news.

Reforming instead of defunding

When it comes to public safety reform, for residents, it is less about the money that goes toward funding law enforcement and more about how those dollars are effectively used to create a respectful, trustworthy, and unbiased police force. Additionally, residents want to see the incorporation of well-equipped teams, such as social workers, that can support community protection.

Most residents (58%) do not think the current level of funding for the Chicago Police Department is too high. This may also explain why 58% of Chicago area residents are also opposed to the campaign Defund the Police.** Nevertheless, less than half of all residents (44%) think the police should be brought in to handle situations like mental health patients and the homeless, and the majority (75%) do think there should be more funding for non-policing alternatives, such as social work dispatches, neighborhood patrols, and restorative justice circles.

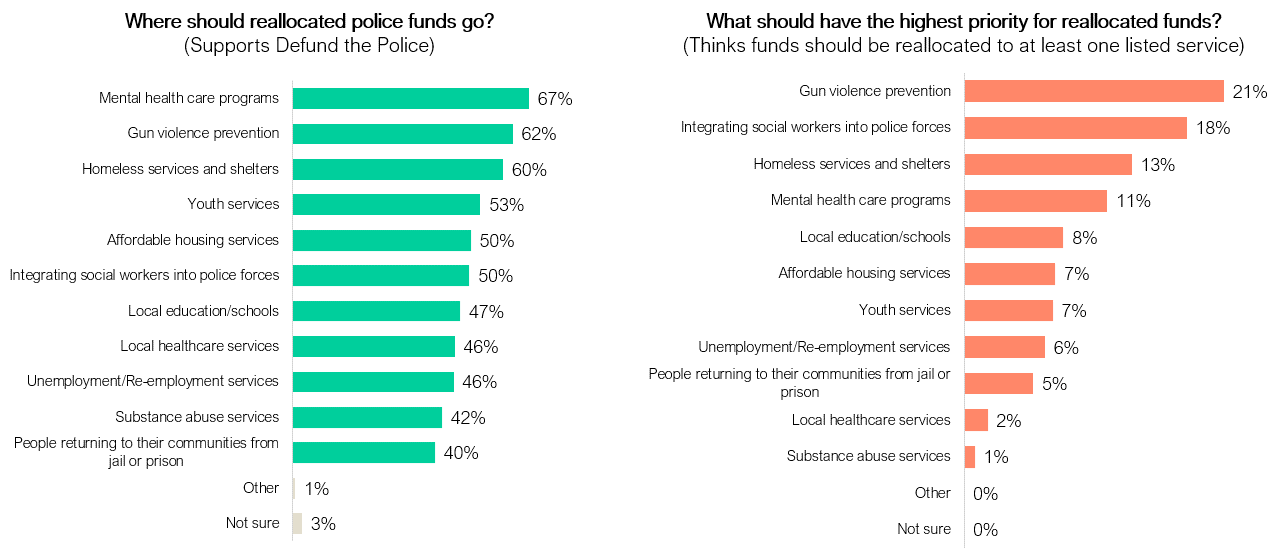

Looking specifically at those who would like to see law enforcement funding reallocated, supporters would like to see more direct financial investment in their communities. The most popular options for reallocated funds were mental health care programs (67%), gun violence prevention (62%), homeless services and shelters (60%), youth services (53%), affordable housing (50%), and integrating social workers into police forces (50%). When asked which services should have the highest priority for reallocated funds, residents mentioned gun violence prevention (21%) and integrating social workers into police forces (18%) most often.

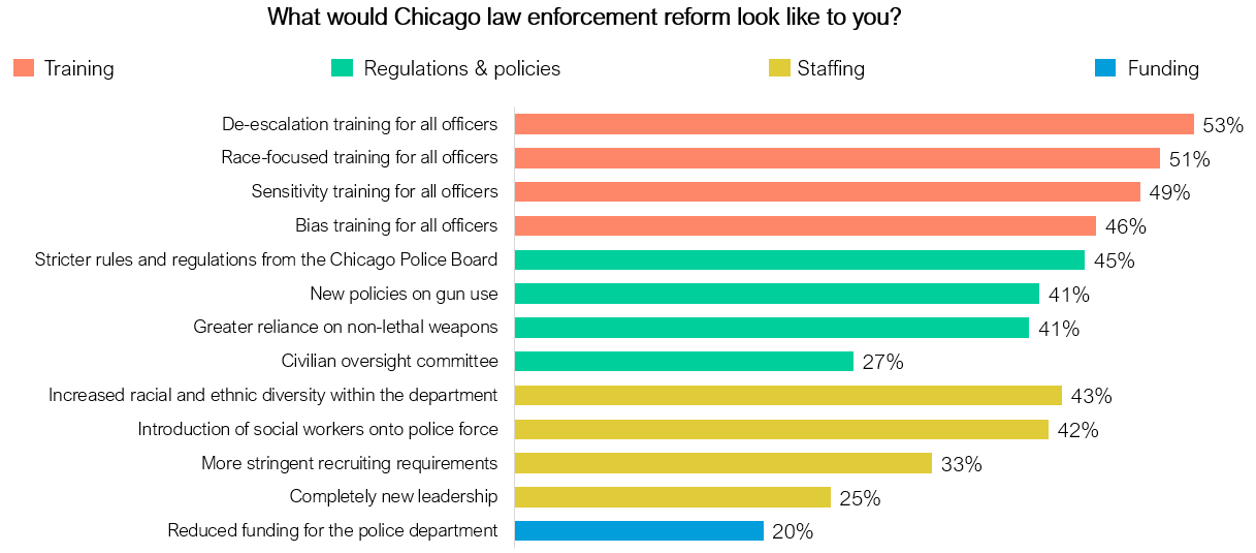

However, the goals of the Defund the Police movement can serve as a guide to city leadership on potential public safety solutions. Although most residents are opposed to police department defunding, they do agree the department needs reform (76%). Chicago residents want to see relationship-focused training, stricter regulations, and staffing changes as the primary tactics for creating law enforcement reform before pursuing solutions related to department funding.

When asked what law enforcement would like to them, only 20% of these residents suggest reduced funding for the police department. However, more than double the number of residents support de-escalation training (53%), race-focused training (51%), sensitivity training (49%), and bias training (46%) for all officers. Additionally, two in five residents also want to see new policies on gun use and less reliance on lethal weapons (41%) as well as a greater push for racial diversity within the department (43%).

Ultimately, in the eyes of Chicago residents, solutions to key city issues start with leadership and reform. With regards to gun violence, residents believe the city should pursue options harnessing legislation, law enforcement involvement, and community support programs. With regards to law enforcement, residents want to see more investment and development in training, new policies and regulations on police department best practices, and adjustments to staffing. Although reallocating police department funds may not be the best course of action, city leadership can show they understand the need for non-policing alternatives by expanding Chicago public safety services to include experts in mental healthcare, gun violence prevention, neighborhood and housing standards, and social work.

*There is concern about how correctly or incorrectly “outside agitators” have been used as a narrative for causing protests to become more controversial and rowdier. The findings from this research should not be interpreted as defining who is actually responsible for the CPD’s approach, nor should this study be specifically interpreted as stating that outside agitators were responsible. Findings should be interpreted as what residents’ opinions are about who should be held accountable based on their personal experiences and external influences, such as the news.

**Note, this was measured in March 2021. This number is an aggregate, weighted value of all Chicago area (both city and suburb) residents. Support and opposition for Defund the Police varies by specific demographics, such as race/ethnicity, age, urban level, and household income. Before indicating their support or opposition, residents were given a brief description of Defund the Police: “Perhaps you have heard of the campaign ‘Defund the Police,’ which refers to the movement to reduce police department budgets and redistribute those funds towards essential social services that are often underfunded, such as housing, education, employment, mental health care, and youth services. Given this understanding, how much do you support or oppose this campaign?”

Methodology

This survey was conducted online within the United States between March 1, 2021, and March 12, 2021, among 997 adults (aged 18 and over) in the Chicago DMA by The Harris Poll on behalf of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Figures for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, region and household income were weighted where necessary to bring them into line with their actual proportions in the population. Propensity score weighting was used to adjust for respondents’ propensity to be online.

All sample surveys and polls, whether or not they use probability sampling, are subject to multiple sources of error which are most often not possible to quantify or estimate, including sampling error, coverage error, error associated with nonresponse, error associated with question wording and response options, and post-survey weighting and adjustments. Therefore, the words “margin of error” are avoided as they are misleading. All that can be calculated are different possible sampling errors with different probabilities for pure, unweighted, random samples with 100% response rates. These are only theoretical because no published polls come close to this ideal.

Respondents for this survey were selected from among those who have agreed to participate in our surveys. The data have been weighted to reflect the composition of Chicago’s adult population. Because the sample is based on those who agreed to participate in the online panel, no estimates of theoretical sampling error can be calculated. For more information on methodology, please contact Dami Rosanwo.

Subscribe for more Insights

Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest trends in business, politics, culture, and more.

Download the Data

Get the full data tabs for this survey conducted online within the United States by The Harris Poll on behalf of the MacArthur Foundation between March 1, 2021, and March 12, 2021, among 997 adults (aged 18 and over) in the Chicago DMA.

Download

Subscribe for more Insights

Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest trends in business, politics, culture, and more.

Download the Data

Get the full data tabs for this survey conducted online within the United States by The Harris Poll on behalf of the MacArthur Foundation between March 1, 2021, and March 12, 2021, among 997 adults (aged 18 and over) in the Chicago DMA.

DownloadRelated Content